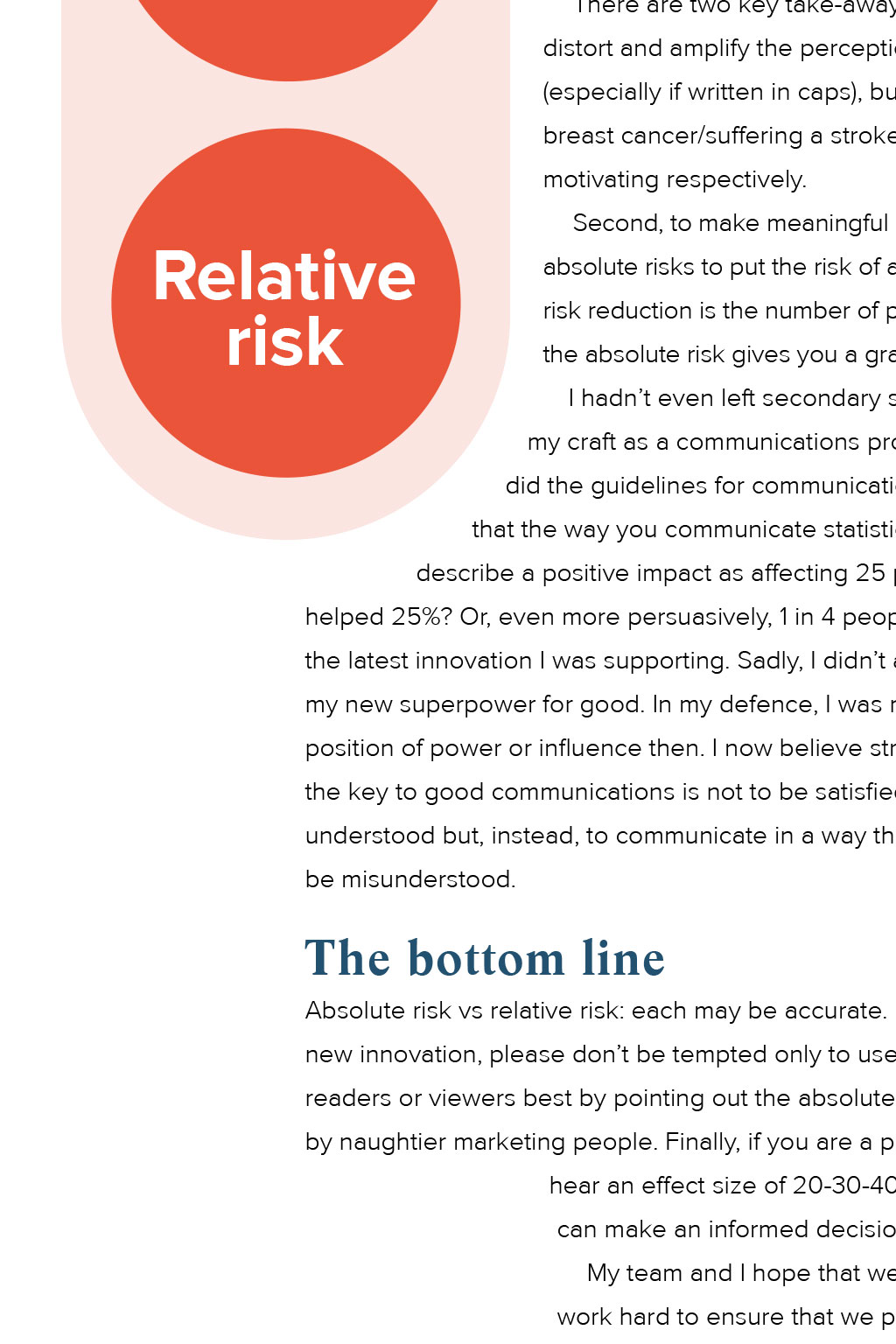

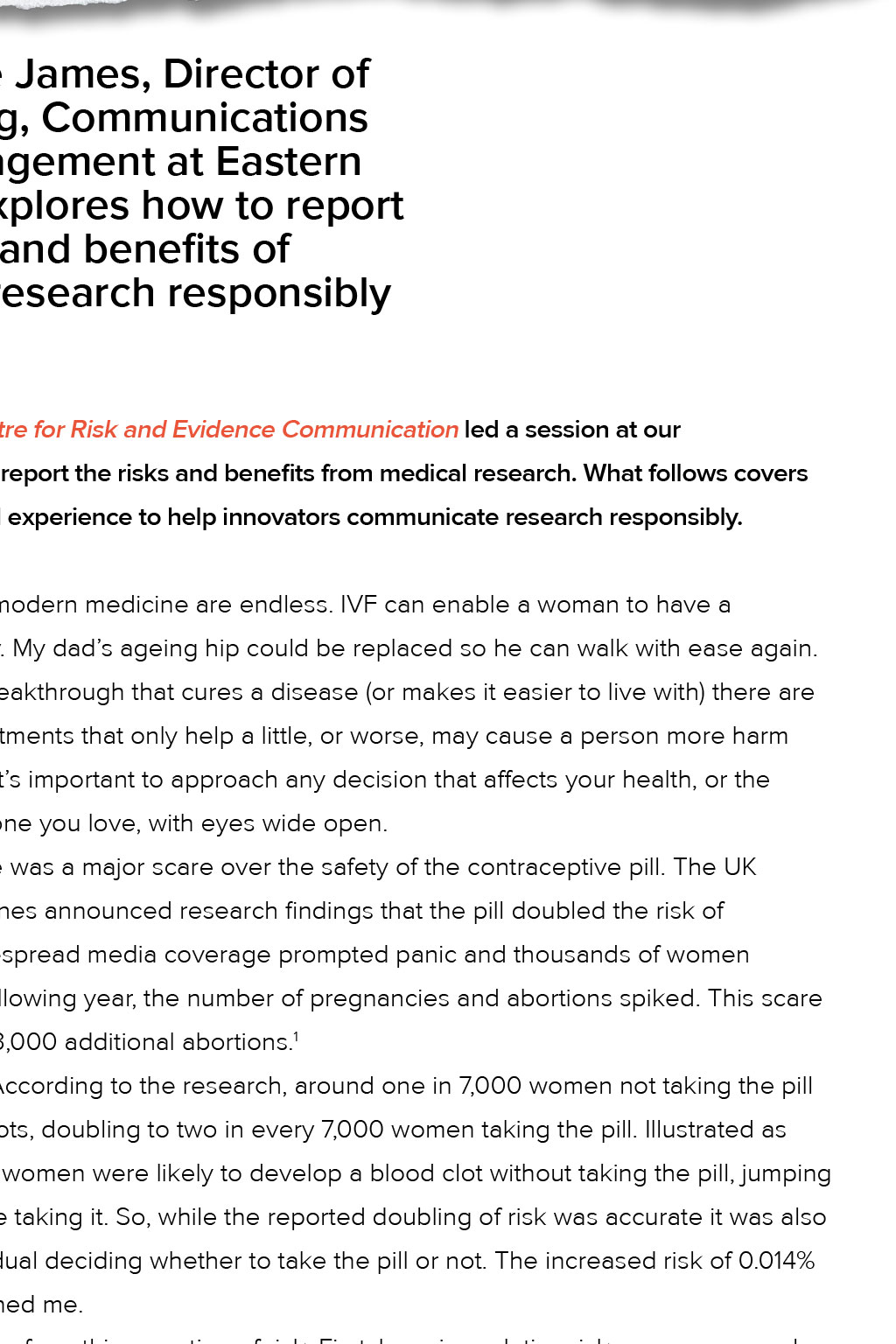

Focus on: marketing and communications The risky business of reporting risks and benefits Charlotte James, Director of Marketing, Communications and Engagement at Eastern AHSN, explores how to report the risks and benefits of medical research responsibly Last January, Dr Alex Freeman from The Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication led a session at our regional leaders innovation forum exploring ways to report the risks and benefits from medical research. What follows covers T a glimpse of what Alex talked about and my personal experience to help innovators communicate research responsibly. Why the numbers matter he wonders of modern medicine are endless. IVF can enable a woman to have a longed-for baby. My dads ageing hip could be replaced so he can walk with ease again. But for every breakthrough that cures a disease (or makes it easier to live with) there are many more treatments that only help a little, or worse, may cause a person more harm than good. So, its important to approach any decision that affects your health, or the health of someone you love, with eyes wide open. In 1995, there was a major scare over the safety of the contraceptive pill. The UK Committee on the Safety of Medicines announced research findings that the pill doubled the risk of potentially fatal blood clots. Widespread media coverage prompted panic and thousands of women stopped taking the pill. In the following year, the number of pregnancies and abortions spiked. This scare alone has been credited with 13,000 additional abortions.1 So, was the panic justified? According to the research, around one in 7,000 women not taking the pill were likely to develop blood clots, doubling to two in every 7,000 women taking the pill. Illustrated as New wonder drug reduced heart attacks from 2 in 100 to 1 in 100 percentages, around 0.014% of women were likely to develop a blood clot without taking the pill, jumping Absolute risk to a whopping 0.028% for those taking it. So, while the reported doubling of risk was accurate it was also wildly misleading. For an individual deciding whether to take the pill or not. The increased risk of 0.014% certainly wouldnt have concerned me. There are two key take-aways from this reporting of risk. First, by using relative risks, you can grossly distort and amplify the perception of a risk. A TRIPLING of risks or benefits might make you gasp (especially if written in caps), but a change from 1 in 100,000 people to 3 in 100,000 people developing breast cancer/suffering a stroke/surviving bird flu (or whatever) is much less knee-shakingly terrifying or motivating respectively. New wonder drug reduces risk of heart attack risk by 50% Second, to make meaningful decisions about healthcare, you need to present the audience with the Relative risk absolute risks to put the risk of an action in context. Absolute risk is the size of your own risk and absolute risk reduction is the number of percentage points your own risk goes down if you do take an action. Only the absolute risk gives you a grasp of the real magnitude and helps you decide if you need to act. I hadnt even left secondary school when the pill scare of 1995 was published but when I was learning my craft as a communications professional, I was not shown this story as an example of what not to do, nor did the guidelines for communications and marketing address this important issue. Instead, I quickly learnt that the way you communicate statistics would influence how the data was perceived. Why describe a positive impact as affecting 25 people in 100, when I could write that it l l i p r e g helped 25%? Or, even more persuasively, 1 in 4 people benefitted from the latest innovation I was supporting. Sadly, I didnt always use my new superpower for good. In my defence, I was not in a position of power or influence then. I now believe strongly that the key to good communications is not to be satisfied with being understood but, instead, to communicate in a way that cannot n a D be misunderstood. The bottom line Absolute risk vs relative risk: each may be accurate. But one may be terribly misleading. If your job is marketing manager for a new innovation, please dont be tempted only to use the relative risk reduction. If youre a journalist, you would serve your readers or viewers best by pointing out the absolute risk reduction and making sure you dont echo any mismatched framing by naughtier marketing people. Finally, if you are a patient, it is wise for you to be sceptical and ask of what? anytime you hear an effect size of 20-30-40-50% or more. 50% of what? Thats how you get to the absolute truth and can make an informed decision. Furedi, A., (1999). The public health implications of the 1995 pill scare. Human Reproduction Update [online]. 5(6), 621-626. [Viewed 18th June 2020]. Available from https://doi.org/10.1093/ humupd/5.6.621 1 Reference Share this article My team and I hope that we can contribute to a more responsible style of communications and we work hard to ensure that we present product and service benefits in a clear and motivating way for the ultimate benefit of patients. To support communications professionals or journalists who want to provide absolute risks, Alexs group at the Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication has developed an online calculator called RealRisk. Get in touch If you would like more advice on how to communicate the risks and benefits responsibly in your communications, please get in touch charlotte.james@eahsn.org