Design is much more than making things look good. Design has been described as what happens when people use creativity to solve problems. When people think about design, they often think about traditional applications, such as communications, products and buildings, but it is increasingly used by the government, the NHS and organisations to rethink and help shape services, systems and policies. In health and care settings, amidst a wide range of complex challenges, design approaches can help create new partnerships, develop new ways of doing things and bring together people who would not normally collaborate, to generate new ideas. The process is often referred to as ‘co-design’. In 2022, NHS England published statutory guidance for working in partnership with people that recognised the value of approaches such as co-design and co-production for improving health outcomes, driving value for money, better decision-making, improving quality, accountability and transparency and addressing health inequalities.

But what is co-design exactly? And, how might someone go about co-designing? Co-design is an approach to actively involving people in the design of services, strategies, policies and processes that impact their lives. Within co-design for health and care, patients and stakeholders should actively take part in the design of an intervention, such as a service, policy, or experience. Co-design has been described as containing three important ingredients; overarching principles or a mindset (e.g. people are experts in their own lives and can create ideas), processes (using the stages of a design process) and practical activities (the subject of this blog).

To help illustrate how these ingredients of co-design come together, I have shared examples from my research, including a co-design approach used in a study called PARITY (Prehabilitation for Cancer Surgery: Quality and Inequality) at Lancaster Medical School. Prehabilitation often focuses on physical activity, diet, and psychological support to prepare cancer patients for their treatment. The study is researching problems of variation and inequality in prehabilitation before cancer surgery in the UK. It is seeking to understand what patients want from prehabilitation by involving people with lived experience and healthcare professionals in co-designing criteria for quality evaluation.

For creating and delivering a co-design approach in the PARITY study, I drew on design research, as well as my experience of research into co-design – particularly for working with underserved communities. We recruited thirty-two people to take part in a series of in-person workshops. Participants included those frequently underrepresented in research, including Deaf people, people with long-term illnesses, and participants from diverse socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds. Through this approach, the team aimed to understand the relationship between prehabilitation programmes and health inequalities.

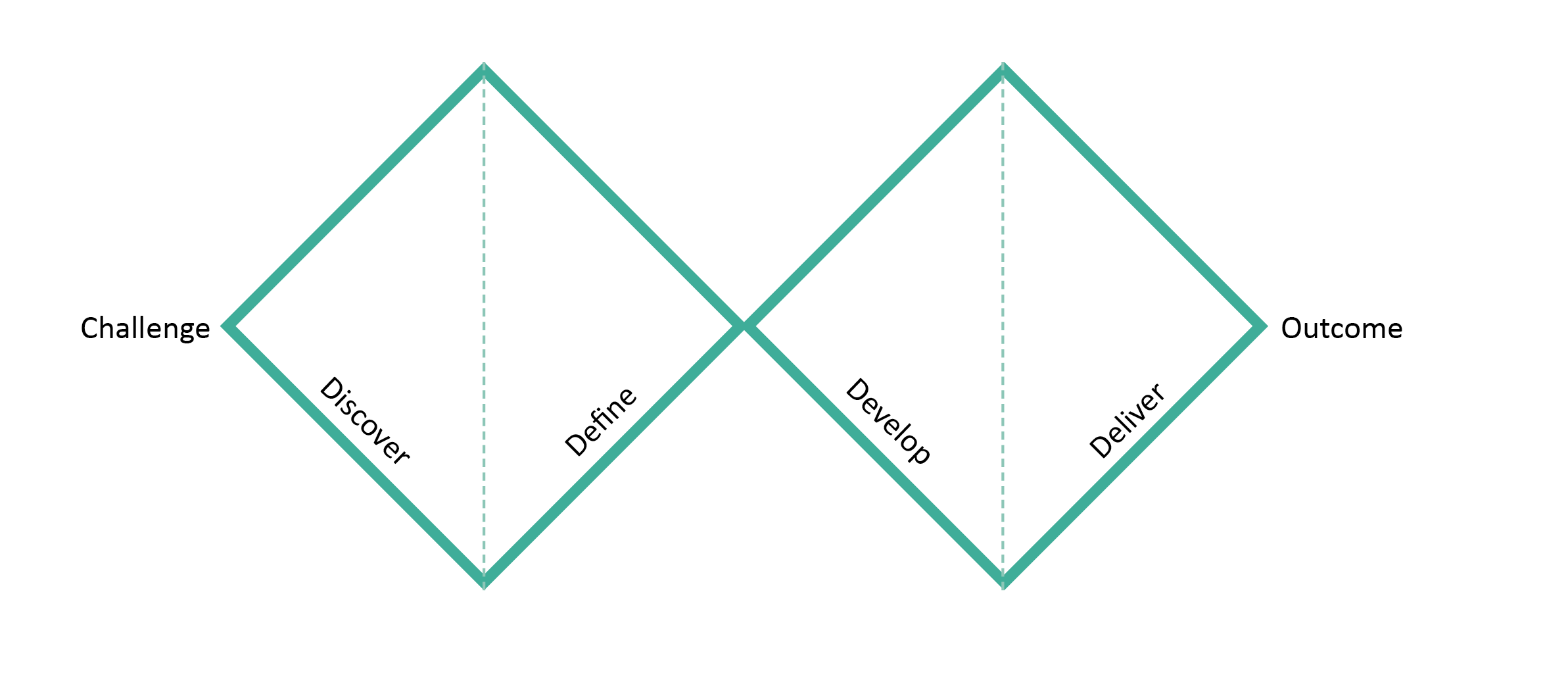

The PARITY team decided what the workshops had to achieve overall and what the co-designers would have to collectively share and discuss to support idea generation. In a process similar to the widely used Design Council’s Double Diamond, we encouraged divergent and convergent thinking, moving through stages referred to as ‘discover’, ‘define’, ‘develop’ and ‘deliver’. To begin any design process, it is important to spend time exploring and discovering what the problem space is before making assumptions, and then working through stages to eventually develop and test ideas.

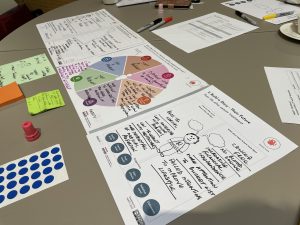

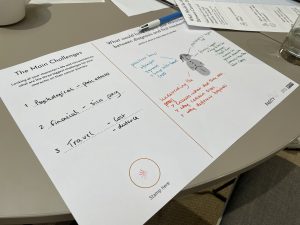

A number of ‘co-design tools’ were designed specifically for the project. Co-design tools can help people to articulate, visualise and share their ideas. The co-design tools were used to structure co-design activities and guide everyone through a design process together. For example, a particular tool guided participants to imagine a character on their cancer treatment journey, including their values and challenges. The tools prompted the groups to think more deeply about ideal prehabilitation services, such as where it should take place, how, who would be involved and how they might overcome barriers to access. The co-design tools could be adapted for other health service co-design projects, particularly where criteria or principles are developed to address health inequalities.

In the PARITY study, the co-design approach took everyone on a journey together. It encouraged people from very different backgrounds to think about and articulate what was valuable in cancer patients’ lives, and challenges and inequalities stemming from peoples’ backgrounds, needs and geographical locations. The co-designed criteria will be used to evaluate prehabilitation programmes across the UK and the research has recently been accepted as evidence for a parliamentary inquiry on Cancer Innovation.

Here are six points that you may find useful to consider for your own co-design approaches:

– Establish aims and opportunities: What are your aims for the process? Are there any opportunities for participants to genuinely influence the outcomes of the process? If not, another approach may be more suitable.

– How will you work: What are your guiding principles for your co-design approach? Who has the power in the process? How is the process inclusive and accessible?

– Designing the co-design: What does the overall co-design journey look like? What will your co-designers need to share and discover together to be able to understand the context, let go of assumptions and design together?

– Consider the gains: What are the mutual learning and benefits opportunities? What do you want to gain from designing with diverse groups, and what can you do to make sure that co-designers gain something from their participation?

– Embedding co-design in community: How might you create sustainable and embedded co-design approaches in your organisation, or in the communities you work with? How can you keep people involved and up-to-date on the progress of the project?

– Be ‘design-led’: Finally, how can you include the design part of co-design, and not just the ‘co’ part (collaborative/collective)? If a design-led co-design approach is a little overwhelming, what about using design approaches to inspire parts of your process? Could you consider collaborating with a designer or design organisation with experience in design for healthcare or social change?

For further inspiration, organisations carrying out interesting work in the design for health space in the UK include The Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design, Lab 4 Living, Snook, Shift, Healthcare Improvement Scotland and The Design Council. Some international examples include; Experio Lab, DXHRI Lab and Health Design Lab.

About the author

Dr Laura Wareing is a Senior Design Researcher working at Lancaster Medical School at Lancaster University. Laura has professional training and experience in design, and a PhD in design from ImaginationLancaster, a design-led research centre at Lancaster University. She has over 10 years of experience working on co-design focused design research. Laura’s research interests include the use of authentic design-led co-design approaches, using design approaches to address inequalities and designing with the public, patients and professionals to improve services. Laura currently works on a National Institute for Health and Care Research funded project called PARITY – Prehabilitation for Cancer Surgery: Quality and Inequality, and with the Lancashire and South Cumbria New Hospital Programme.

References

- Cooper, R. and Tsekleves, E. (2017) Design for health. London: Routledge.

- Design Council (2020) Using design to reduce health inequalities. Available at: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/fileadmin/uploads/dc/Documents/Health%2520and%2520Wellbeing%2520Roundtable%2520Summary.pdf

- Heiss, L. and Kokshagina, O., (2021) Tactile co-design tools for complex interdisciplinary problem exploration in healthcare settings. Design Studies, 75, p.101030.

- King, P.T., Cormack, D., Edwards, R., Harris, R. and Paine, S.J. (2022) Co-design for indigenous and other children and young people from priority social groups: A systematic review. SSM-Population Health, 18, p.101077.

- Ku, B. and Lupton, Ellen (2022) Health Design Thinking, Second Edition : Creating Products and Services for Better Health. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Nesta (2013) By Us, For Us: The Power of Co-design and Co-delivery. London: Nesta. Available at: https://www.nesta.org.uk/report/by-us-for-us-the-power-of-co-design-and-co-delivery/

- Rygh, K. and Clatworthy, S., (2019). The use of tangible tools as a means to support co-design during service design innovation projects in healthcare. Service design and service thinking in healthcare and hospital management: Theory, concepts, practice, pp.93-115.

- Steen, M., Manschot, M. and De Koning, N. (2011) Benefits of co-design in service design projects. International Journal of Design, 5(2).

Share your idea

Do you have a great idea that could deliver meaningful change in the real world?

Get involved